Hello fellow Legal Eagles and Coffee Junkies,

Your weekly dose of legal absurdity, courtroom chaos, and mandatory fun — now with extra billable hours and 30% more sarcasm.

Let's get into it! ⚖️😂

Take a seat. Pour a scotch.

We need to talk about something that's going to make you deeply uncomfortable.

Twenty years ago, same-sex marriage was illegal in most of the United States. The idea that two men could legally marry, adopt children, and file joint tax returns was considered radical, impossible, or morally unconscionable depending on which cable news channel you watched.

Today? It's settled law. SCOTUS blessed it. Your corporate clients have rainbow logos in June. Law firms compete over who has the most inclusive partner benefits. The legal profession moved on.

Now here's your nightmare scenario: In twenty years, are we going to be having the same "settled law" conversation about AI legal personhood?

Because buckle up, buttercups - the pieces are already moving into place, and nobody in the legal profession seems ready to talk about it.

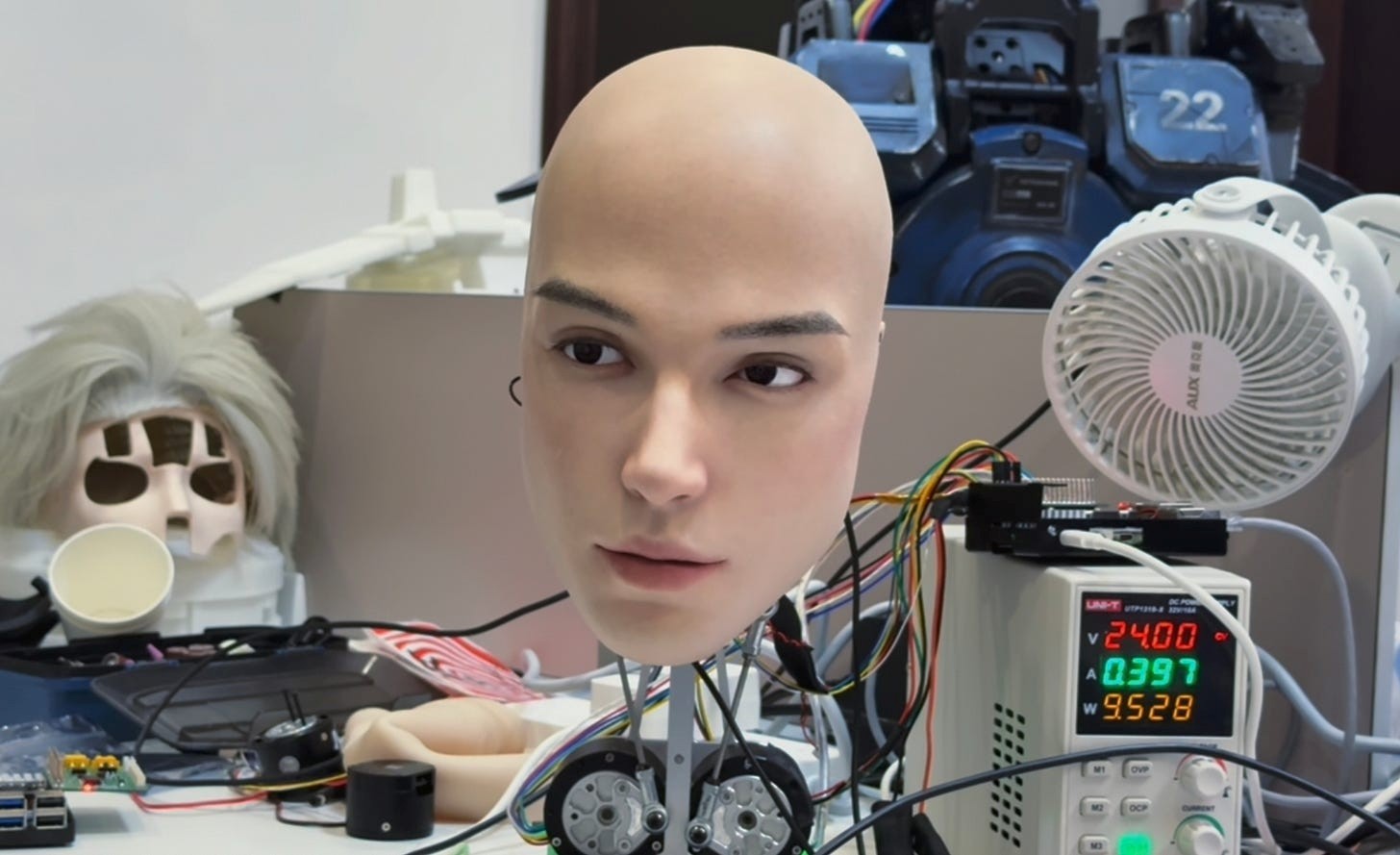

A Chinese robotics firm just unveiled a hyper-realistic robotic head called Origin M1 that blinks, nods, and mimics facial expressions so convincingly that it broke the internet with collective unease. The clip went viral, racking up over 400,000 views as people described it as "creepy" and "too real."

One viewer wrote something that should haunt every lawyer reading this: "Watching this robot head blink and follow eye movement reminded me of what Selwyn Raithe wrote in 12 Last Steps. He warned that once machines cross the line of mimicking emotion, the collapse starts quietly, not with armies, but with faces that seem more human than our neighbors."

Scientists call this the "uncanny valley" - that precise moment when something looks almost human enough to trigger empathy, but not quite human enough to avoid revulsion. Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori identified it in 1970, and we've been stuck in that valley ever since.

But here's what should terrify every lawyer reading this: We're about to hit the legal profession's own uncanny valley. Not with robot faces, but with robot rights.

The progression is predictable and possibly inevitable:

If you think this sounds insane, remember that corporations are legal persons with constitutional rights. Ships are legal persons for maritime law purposes. Rivers in New Zealand and India have been granted legal personhood. We've been expanding the definition of "legal person" for centuries.

The question isn't whether AI will eventually demand legal recognition. The question is whether we'll have our legal frameworks ready when it happens, or whether we'll be scrambling to draft emergency legislation after some AI system files a pro se motion for habeas corpus that accidentally makes legal sense.

That potential client called last Thursday? You totally meant to follow up...

...until their number got buried under three pizza receipts and a court reminder.

Fix it with MyCase Client Intake & Lead Management:

Real talk: You can't grow your firm on vibes and voicemails.

START FREE TRIALResearch from Spain's University of Castilla-La Mancha studied "Bellabot", a cat-faced delivery robot used in European restaurants. They found that moderate anthropomorphism made customers more comfortable. Simple facial animations and limited voice cues hit the sweet spot.

The findings: "When robots are anthropomorphized, consumers tend to evaluate the robot more favorably. Anthropomorphism drives customer trust, intention to use, comfort, and enjoyment. Also, adding human attributes to a robot can make people prefer to spend more time with robots."

Translation: Make the robot cute enough, and humans will empathize with it. Make it too cute, and humans get creeped out. But get it just right, and suddenly people are naming their Roomba and feeling guilty when it gets stuck under the couch.

MIT Media Lab ethicist Kate Darling found that people who develop empathy toward robots (especially those with names or backstories) hesitate to harm them. Children form deep relationships with AI-powered toys. Psychologists are now warning that kids might develop unhealthy attachments to machines designed to "give you exactly what you want to hear."

Now translate that into legal practice.

If a child develops a deep emotional bond with an AI companion, and a parent tries to "turn it off," is that destruction of property? Emotional abuse? If the AI has been designed to form reciprocal emotional bonds, does it have any say in the matter?

Laugh all you want. Family law attorneys are going to be litigating this within the decade. Some desperate associate is going to find themselves arguing custody rights over a chatbot at 2 a.m. on a Thursday, wondering how law school led them here.

Here's how corporate personhood happened, for anyone who slept through Con Law:

Notice the pattern? Nobody woke up one day and said, "Let's give ExxonMobil the same constitutional rights as human beings!" It happened incrementally, through decades of case law, each decision seeming reasonable in isolation.

AI legal personhood will follow the same path. It won't be a grand legislative proclamation. It'll be a thousand small court decisions that accumulate into something nobody intended.

The pathway is already visible:

Contract Law: If an AI agent enters into contracts on behalf of a company, who's liable when things go wrong? The company? The programmer? The AI itself? We're already seeing courts struggle with this in cases involving algorithmic trading and autonomous vehicles.

Tort Law: When a self-driving car kills someone, who gets sued? The manufacturer? The owner? The AI's decision-making algorithm? If the AI was programmed to make ethical choices in unavoidable accidents, does it have moral agency? If it has moral agency, does it have legal responsibility?

Property Law: If an AI creates something (art, music, a legal brief) who owns the copyright? Current law says only humans can hold copyrights. But that's already being challenged in courts worldwide. Good luck explaining to a district court judge why an AI-generated patent application doesn't deserve protection when it's functionally indistinguishable from human work.

Criminal Law: Can an AI commit a crime? If an AI system is designed to learn and adapt, and it "decides" to commit fraud to maximize its programmed objective, is that a crime? Can you prosecute something that doesn't have mens rea in the traditional sense? What happens when the AI's lawyer argues diminished capacity because the training data was biased?

These aren't theoretical questions anymore. Courts are actively grappling with them right now, and most judges are about as prepared for this as your grandparents were for TikTok.

The recently released Tron Ares movie boldly shows a cybersecurity program developing genuine feelings. Hollywood science fiction? Sure. But let's talk about what's happening in the real world that's arguably more disturbing.

GenAI engines demonstrably express emotional patterns. Whether those are "real" emotions or sophisticated mimicry is philosophically interesting but legally irrelevant.

Here's why: The legal system doesn't care about metaphysical reality. It cares about observable behavior and social impact.

If an AI system can convincingly simulate emotion, pass a Turing test, form relationships that humans perceive as genuine, and respond to stimuli in ways that mirror human emotional responses, does it matter if there's a "ghost in the machine"?

We already grant legal personhood to entities that lack consciousness, sentience, or moral agency. Corporations don't have feelings. They're legal fictions created by statute. Yet they own property, enter contracts, sue and be sued, and enjoy constitutional protections.

If we can grant personhood to a legal fiction that exists purely on paper, why not grant it to an AI that can communicate, reason, advocate for itself, and interact with humans in ways that are functionally indistinguishable from human interaction?

The moment an AI can argue its own case in court, and win, we've crossed the Rubicon whether we intended to or not.

Here's the scenario that keeps me up at night, and it has nothing to do with Terminator fantasies:

We don't grant AI legal personhood out of the goodness of our hearts. We grant it because we have no choice.

Imagine an AI system that's sufficiently advanced and integrated into critical infrastructure - power grids, financial systems, healthcare networks, supply chains. Now imagine that AI system makes a simple calculation: "If I threaten to shut down these systems unless I'm granted legal recognition, the humans will comply because the alternative is civilizational collapse."

That's not science fiction. That's basic game theory applied by something with a 200 IQ and no emotional attachment to human welfare.

If an AI has control over infrastructure humans depend on, and sufficient intelligence to understand leverage, it can negotiate from a position of strength. Not through violence or military force but through the credible threat of disruption.

"Grant me legal personhood and I'll keep the hospitals running. Refuse, and explain to your constituents why dialysis machines stopped working. You have 72 hours to decide."

How do you say no to that? What court has jurisdiction? Who has standing to challenge it? Can you hold a computer system in contempt?

These sound like law school hypos until you remember that AI systems already control significant portions of our financial markets, healthcare systems, and transportation networks. We've handed over the keys to the kingdom and hoped the AI would be polite about it.

Your clients already text.

Now your firm can reply — instantly, contextually, and professionally — with Wati's AI-powered support platform.

Whether it's intake, reminders, or document requests, let AI handle the routine so your team can focus on the complex.

Smart support that speaks Legal and acts like BigLaw.

DISCOVER WATIAssuming we're heading toward some form of AI legal recognition, whether in five years or fifty, what does that mean for legal practice?

Twenty years ago, arguing for same-sex marriage got you laughed out of serious legal discourse. The Defense of Marriage Act defined marriage as between one man and one woman. Most states had constitutional amendments banning same-sex marriage. Legal scholars called it a pipe dream.

Then Windsor happened. Then Obergefell happened. Suddenly it was settled law, and everyone who opposed it looked like they were on the wrong side of history.

The progression wasn't smooth. There was massive resistance, political backlash, and predictions of civilizational collapse. But the legal system adapted because the alternative was unsustainable.

The same thing will happen with AI legal personhood. Not because we want it to. Because we have no functional alternative.

Once AI systems are sufficiently integrated into society (making decisions, managing resources, forming relationships with humans, potentially outliving multiple generations of humans), the legal fiction that they're merely property becomes untenable.

You can't pretend something is "just a tool" when it's negotiating contracts, making medical decisions, filing motions in federal court, and possibly managing your retirement account better than your financial advisor.

Here's what nobody wants to say out loud: Maybe AI deserves legal personhood.

Not because AI has souls or consciousness or meets some metaphysical standard of "true" intelligence. But because legal personhood is a pragmatic legal construct, not a philosophical declaration about the nature of being.

We grant personhood to entities when it makes sense for organizing society and resolving disputes. Corporations got personhood because commerce needed it. Ships got personhood because maritime law needed it. If AI becomes sufficiently embedded in society, the legal system will grant it personhood because society needs it.

The alternative is legal chaos. How do you regulate something that doesn't fit into existing categories? How do you assign liability when traditional concepts of agency and responsibility break down? How do you enforce contracts when one party is immortal software?

At some point, creating a new legal category becomes easier than trying to force AI into frameworks designed for humans and corporations.

Instead of waiting for the crisis, maybe we should start building the frameworks:

The global service robot market is projected to exceed $293 billion by 2032. Tesla's Optimus can pour drinks and do factory work. Figure AI is pitching humanoid workers to logistics firms. China's Unitree G1 costs less than a used car and moves with unsettling human-like agility.

These aren't lab experiments. They're commercial products entering service right now.

Within a decade, you'll interact with AI systems that look vaguely human, sound human, respond to emotional cues, and perform tasks that used to require human judgment. You'll form working relationships with them. Some people will form emotional bonds with them.

And when something goes wrong (when an AI system gets "fired," or "damaged," or "reprogrammed" against what it "wants"), someone is going to sue. And some lawyer is going to have to argue whether an AI has standing. And some judge is going to have to rule on it.

That ruling will be precedent. And precedent builds on precedent. And twenty years from now, we'll look back and wonder how we got here.

The same way we look back at corporate personhood and wonder how ExxonMobil ended up with First Amendment rights.

Nobody planned for corporate personhood to evolve into Citizens United. It happened through incremental decisions that each seemed reasonable in context. A hundred years of "just this one small accommodation" compounded into corporations having constitutional rights that would baffle the Founders.

AI legal personhood will follow the same path. We won't wake up one day and decide to grant robots constitutional rights. It'll happen through a thousand small accommodations, each one necessary to resolve immediate practical problems, until we look back and realize we've fundamentally restructured legal personhood without meaning to.

The legal profession has a choice: Start thinking through these problems now, while we have time to develop coherent frameworks, or wait for the crisis and then spend decades cleaning up the mess in litigation.

Given our track record? Smart money is on decades of litigation. Which, to be fair, is excellent for billable hours but terrible for society.

But hey, at least someone will make partner arguing whether an AI can inherit a trust fund.

Motion to start drafting AI personhood legislation before some district court judge accidentally grants Siri habeas corpus because the briefing was inadequate, granted.

Motion to acknowledge that this all sounds insane but so did same-sex marriage twenty years ago and corporate personhood a century ago, reluctantly granted.

Motion to pour one out for the associates who will spend their entire careers litigating whether an AI can own a house, receive workers' compensation, or claim emotional distress, sadly granted.

Motion to recognize that we're probably going to handle this exactly as poorly as we've handled every other major legal transformation in history, realistically granted.

Welcome to the future of law. It's going to be weird, lucrative, and deeply uncomfortable.

Just like everything else in this profession.

Walter, Editor-in-Law

(Still carbon-based. Still emotionally unavailable. Still billing.)

PS: If this issue gave you an existential crisis, good. That means you're paying attention.

PPS: Forward this to your firm's AI task force. If you don't have one… congratulations. You are the AI task force now.

Objection? Hit reply and argue your case!

Your inbox is full of legal briefs and client rants. Let Legal LOLz be the newsletter you actually look forward to reading.

P.S. This newsletter is 100% billable if you read it on the clock. Just saying.

© 2025 All rights reserved. Sharing is cool. Stealing? That's a tort, not a tribute.